From the outset, even though he was working “in symbiosis”, as he put it, with the Société des Missions Evangéliques de Paris, Schweitzer wanted his work to be “supra-denominational and international”, convinced as he was that “any humanitarian task in colonial lands (we would say today: in Third World countries) is the responsibility not only of governments or religious societies, but of humanity as such” (On the edge of the primeval forest). In short, at the beginning of the century, Schweitzer had already conceived – and applied – the idea of NGOs – Non-Governmental Organisations – to help countries in distress.

Arrival at Lambaréné

On Good Friday 21 March 1913, Hélène and Albert Schweitzer left Gunsbach and embarked for Bordeaux on 26 March. They arrived in Lambaréné on 16 April, where they were given a friendly welcome by the missionaries at the Andendé station, where it was impossible to find the labour needed to build a simple corrugated iron hut. The okoumé wood trade paid much better and was unbeatable competition at the time.

It was the tom-tom that announced the arrival of the doctor and, despite the three weeks the missionaries asked the natives to allow the “great doctor” to settle in, he was so successful right away that Schweitzer had to use his house as a pharmacy and set up the operating theatre in an old chicken coop.

Schweitzer was assisted by his wife Hélène and found a valuable helper in Joseph, an African who was Savorgnan de Brazza’s cook. Joseph also acted as a translator for the various languages spoken in the region. In his translations, his cook’s language produced surprising results, such as the famous “elle a mal dans le gigot droit” (“she’s got a pain in the right leg”) and other tasty aphorisms.

Doctor and builder

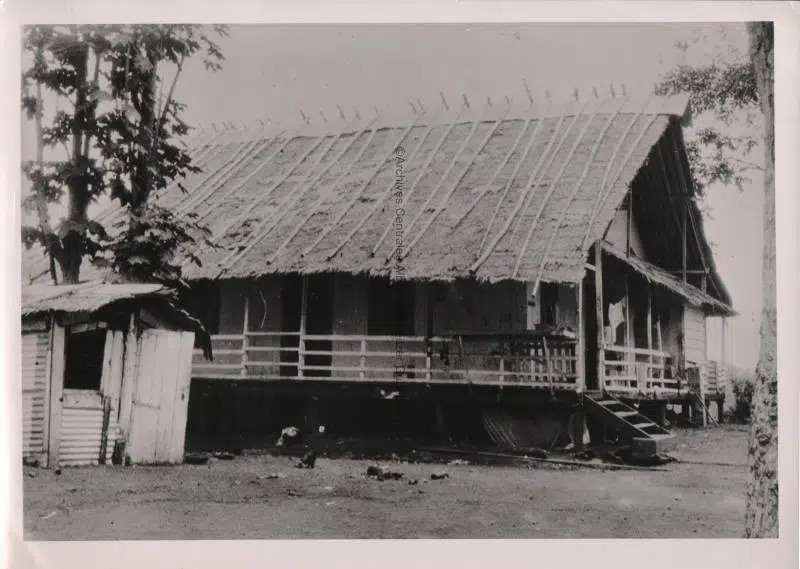

By mid-November, a “real” dispensary could finally be inaugurated, a sheet-metal hut that was relatively cool because it was well ventilated, thanks to Schweitzer’s instructions, which included an opening above the windows, under the canopy roof, allowing the hot air to escape. In December, two more huts were built, a waiting room and a dormitory for the sick. The Mission had finally authorised Schweitzer to build what he deemed necessary on a cleared site at the foot of the hill where he lived, near the River Ogooué.

From the outset, therefore, driven by the emergencies that arose, Schweitzer was both a doctor and a builder, and once the hospital was built and expanded, he naturally became its director, a boss, a leader. In this way, the same man took on three roles that are usually separated and assigned to different people. Once the dormitory building was in place, the patients or members of their families were asked to make their own bed timbers: “four sturdy stakes, ending in forks, on which intertwined wooden logs rest, all tied together with vines”. Dry grass was used as a mattress. It was as simple, as “rudimentary” and elementary as that. Anything else (a European-style hospital) would have been unthinkable, unsuitable and, in any case, financially impossible.

It was in this same state of forced improvisation, responding to the needs of the moment and using the “means at hand”, that the original formula of the hospital-village was “invented”, a formula that would gradually make its founder famous, but which would also, towards the end of his life, lend itself to criticism. With independence and the promise of development, some time after the Second World War, the Africans themselves might want modern hospitals because it was technically feasible, and by comparison they might consider the facilities and operating methods of the Hôpital Schweitzer to be “primitive”, a relic of colonialism. But… the spirit of the times changes very quickly. Now that certain illusions have been dispelled, and the extension of a certain form of modernisation based on the Western model has been called into question, there is greater recognition of the ‘African’ originality of Schweitzer’s work at Lambaréné, and his happy adaptation to the situation, needs and customs of this country, ‘between water and virgin forest’.

The work, begun in 1913, was, as we know, put on hold barely a year and a half later by the world war, and then interrupted in 1917 by the Schweitzer family’s departure from Gabon and temporary internment in France. In those times of upheaval, they might even have feared that it was the end.

Walter MUNZ

(Published in Cahiers Albert Schweitzer N°93, September 1993, p.23-25)